While it may seem like a simple matter, determining how high an airplane is flying is rather complicated. There are at least five different types of altitude that pilots use and think about. Which one is the altimeter reading, and is it even correct? It’s not a question an experienced pilot should have to ponder for long.

Table of Contents

What Does AGL Stand For in Aviation?

Altitude has many different references and definitions in aviation. AGL stands for “above ground level,” and it indicates an altitude using the ground as a reference. This is also known as absolute altitude.

Absolute versus True Altitude, or AGL vs. MSL

The two main types of altitude to consider in aviation are absolute altitude and true altitude. True altitude references height above mean sea level (MSL), while absolute altitude references height above ground level (AGL).

Perhaps surprisingly, pilots spend most of their time concerned with true altitude. When correctly set, the aircraft’s altimeter reads true altitude. All altitudes printed charts and in air traffic control instructions also use true altitude.

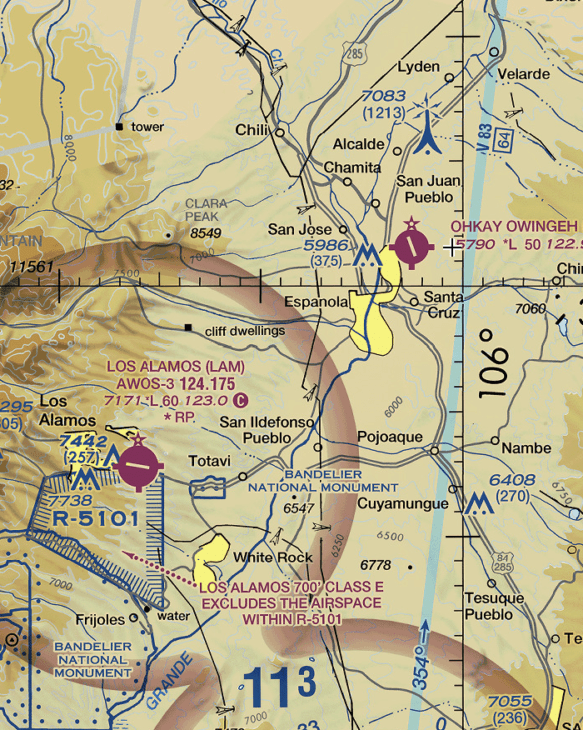

Since the pilot is always referencing MSL, it is up to them to know what ground level is. Land and airport elevations are shown on VFR sectional charts in several ways. Airports have their official field elevations listed. The terrain is depicted topographically and in color. Individual spot elevations are provided, as are the elevations of any lakes. Obstacles have both their MSL and AGL heights provided, so with a quick subtraction, the pilot can calculate the elevation at that spot.

Reviewing field elevation is an integral part of briefing an approach to a new airport. VFR pilots will need to know the appropriate traffic pattern altitude, which is usually 1,000 feet AGL. All pilots will need to know the touchdown zone elevation or the field elevation to gauge their approach to the runway.

This except of the VFR sectional chart from the State of New Mexico includes many examples of MSL and AGL altitudes. The brown colors correspond to land elevations ranging from 6,000 to 7,000 feet above sea level. Several topographic lines can be seen east of Los Alamos, along with several spot elevations in black (6,547 feet MSL and 6,778 feet MSL).

Additionally, the field elevation of the Los Alamos Airport is listed as 7,171 feet above sea level.

Other Types of Altitude

There is more to the altitude equation than just AGL and MSL. Both of these concepts ignore changes in the atmosphere, which occur regardless of where sea level or ground level are located.

There are 5 types of altitude in aviation:

- Absolute altitude in feet AGL ( above ground level)

- True altitude in feet MSL (above mean sea level)

- Pressure Altitude

- Density Altitude

- Indicated Altitude

Pressure Altitude

To accurately gauge how well or poorly the aircraft might perform on a given day, the pilot needs a way to calculate the conditions found in the atmosphere in real-time. Factors that affect the performance of the aircraft include atmospheric pressure and temperature.

Pressure altitude is the aircraft’s altitude when referencing standard atmospheric pressure, which is 29.92” Hg. It may sound random, but this standard datum is used the world over. Pressure altitude can be calculated in two ways. The pilot can take the current altimeter setting, subtracted from 29.92, multiply by 1,000, and then add the field elevation. Alternatively, they could set 29.92 into the altimeter. The indicated altitude is then the pressure altitude.

Both of these methods make the standard assumption that every 1,000 feet are equal to 1.00” Hg of pressure change. Unfortunately, in the real world, this isn’t always true. Temperature can have a significant effect on the distance between pressure levels. On warm days, the pressure levels expand, so that 1,200 feet or more may exist in a 1.00” Hg change.

Density Altitude

To accurately account for this change, density altitude is pressure altitude corrected for non-standard temperatures. Standard temperature is 15 degrees Celcius or 59 degrees Fahrenheit.

The pilot will use one or both of these numbers when reviewing the performance data of the airplane. Chapter Six of the Aircraft Flight Manual contains charts that allow the pilot to input the pressure or density altitude and the aircraft takeoff weight to get critical information. Just a few of the things pilots must compute are takeoff and landing runway length requirements, climb rate, cruise speed, and fuel burn.

Since the pilot is referencing MSL, it is up to them to know what ground level is. Land and airport elevations are shown on VFR sectional charts in several ways. Airports have their official field elevations listed. The terrain is depicted topographically and in color. Individual spot elevations are provided, as are the elevations of any lakes. Obstacles have both their MSL and AGL heights provided, so with a quick subtraction, the pilot can calculate the elevation at that spot.

Reviewing field elevation is an important part of briefing an approach to a new airport. VFR pilots will need to know the appropriate traffic pattern altitude, which is usually 1,000 feet AGL. All pilots will need to know the touchdown zone elevation, or at least the field elevation to help them gauge their approach to the runway.

Flight Levels

At some point, the utility of using sea level as a reference point ceases for aircraft that are well above ground level. In the United States, the transition altitude is 18,000 feet. At this point, all pilots set their altimeters to 29.92” Hg.

They are flying a pressure altitude instead of a true altitude. For clarity, these pressure altitudes are called “flight levels” and are measured in hundreds of feet. FL180 refers to 18,000 feet, while FL350 refers to 35,000 feet.

Flight levels ensure that all aircraft are using the same reference. Imagine airliners flying at 20,000 feet MSL, but one with their altimeter set to Los Angeles and one set to Phoenix. There could be many hundreds of feet of inaccuracy, and there is a risk for collision since the vertical separation between planes cannot be assured.

At lower altitudes, controllers provide their local altimeter settings with every controller change. If this occurred with fast-moving high-level aircraft, they might have to change their altimeter settings every few minutes!

The transition altitude is a random level that depends on the country. While the United States is 18,000 feet, some countries have a transition level as low as 3,000 feet.

Related Posts