One of the really neat things about riding in the passenger seat of an airliner is sitting over the wing and watching all of the plane’s flight controls move during flight. What are they all doing? Everyone has heard of “flaps,” but what exactly are they?

Table of Contents

What Are Flaps?

Flaps are trailing-edge high-lift devices. That’s a technical way of saying that they are movable surfaces on the back of the wings that help the plane make more lift. They’re used to help a high-speed plane fly slowly for takeoff and landing.

What Are Flaps Used For?

Exactly how flaps are used in flight varies from airplane to airplane, depending on its speed profiles and basic design. Nearly all planes use flaps for landing since they help them fly a bit slower than they can without them.

Some planes, however, also use their flaps during takeoff. If a plane has a low profile wing designed for high-speed flight, adding a little bit of flaps will help it get off the ground sooner. Therefore, it will use less runway and rotate off the ground at a slower speed than otherwise.

If a plane does use flaps for takeoff, it would only be a small amount. As flap settings are increased, lift increases–but so does drag. A little bit of extra lift is helpful on takeoff, but any amount of drag is harmful. Some planes entirely prohibit the use of flaps during takeoff, while some planes require a little bit of flaps to be used every time.

On landing, one of the primary benefits of flaps is that they enable the plane to descend quickly without building up airspeed. That means that a pilot can fly a steeper approach than they could without the flaps while maintaining a slow airspeed.

A steeper approach enables the plane to avoid obstacles on the approach path and keep their flight path near the airport. In planes that don’t have flaps, or if the flaps are inoperative, a maneuver called the forward slip to land can help the pilot fly a similar steep approach.

Aerodynamics of Flaps

The lift a wing makes is a factor of two things–the speed of the air flowing over it and its angle of attack (AOA). The AOA is the angle between the wing’s chord line (an imaginary line drawn between the leading edge and the trailing edge) and the relative wind.

Flaps work by moving the trailing edge of the wing downward, which moves the chord line. Without changing the pitch of the plane, flaps create a bigger angle of attack on the wing, and therefore more lift.

But induced drag is also created when the angle of attack increases, so even adding a little bit of flaps adds drag too. As the flaps get lower and lower, they add parasite drag too.

What Are the Four Types of Flaps?

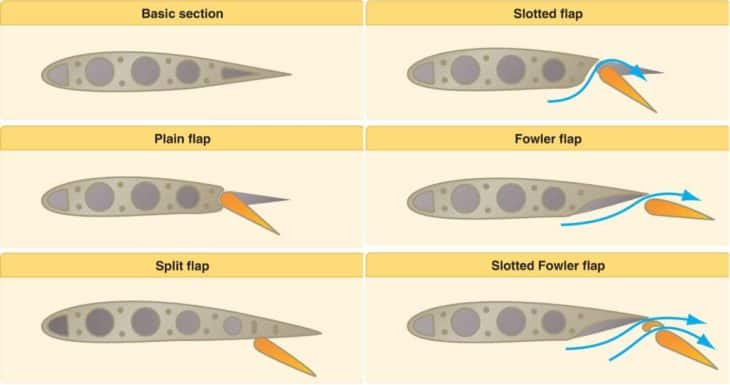

There are four main types of flaps found on planes. Each type is described in detail in the FAA’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge.

Planes often have multiple types of flaps built into them. For example, some light twins have inboard split flaps connected to outboard plain flaps. Airliners often us a combination of slotted and Fowler flaps.

Plain Flaps

Plain flaps look very much like inboard ailerons. They are flight control surfaces made up of the trailing section of the wing’s airfoil. When they are deployed, a small section of the back of the wing deflects downward.

Split Flaps

When a split flap goes down, the top of the wing above it remains the same. Instead of the entire trailing edge of the wing moving, only the bottom section of the wing goes down.

Split flaps are often used in areas where the wing has other structures that make engineering a plain or slotted flap complicated. One example is on twin-engine airplanes, where the engine nacelle extends to or beyond the wing’s trailing edge.

Slotted Flaps

Slotted flaps move away from the main wing slightly, and they are lift-producing airfoils themselves. That means that air can flow over the top of them and below them, so they can add quite a bit of lift compared to other types of flaps.

Fowler Flaps

A Fowler flap is very similar to the slotted, with an aerodynamic flow created over the flap and the wing. But what separates the Fowler from any other sort of flap is that they not only travel down but aft as well. This means that when Fowler flaps are extended, the plane’s wing area increases to make more lift.

Fowler flaps are very common on airliners and planes with substantial speed differences between cruise and terminal operations.

How Do Flaps Work?

Flaps are generally engaged with a simple lever on the control panel. It is usually shaped like a flap to help the pilot distinguish it from other controls when they’re in a hurry.

There have been accidents where pilots accidentally retract the landing gear when they mean to retract the flaps, so the two control are now made to look like a wheel and a flap, respectively.

The actual system that deploys the flaps varies from airplane to airplane. Pilots need to understand their planes’ systems so that they can diagnose any problems with the system.

In some planes, a malfunction could mean a dangerous situation where one side’s flaps deploy while the other sides’s does not. The difference in lift caused by an asymmetric flap deployment would put the plane into a sudden roll.

On small planes, the most common system of flap actuator is an electric motor. When the switch is moved, the motor either spins control tubes that move the flaps or moves a collection of wire ropes on pulleys. If there is an electrical failure onboard the plane, the flaps will no longer function.

Some older planes have a much simpler system. The Piper Cherokee/Warrior series of low-wing planes feature a manual handle actuator. It looks just like the hand brake in a car, and pulling up adds flaps in increments.

Large transport aircraft are more likely to have their flaps move using hydraulic systems. These flaps are enormous, so the system needs a lot of power to move them.

Flap Settings for Takeoff and Landing

Flap settings are generally measured in either degree or incremental settings. For example, the Cessna 172 allows the pilot to select flaps at 0 degrees, 10 degrees, 20 degrees, or 30 degrees.

Other planes may have settings like up, approach, and landing. Those settings correspond to set degrees, of course, but the designers decided to simplify the setup in the cockpit.

The exact settings that the pilot should use for standard maneuvers are laid out in the airplane’s pilot’s operating handbook (POH). The POH is sometimes called the AFM or airplane flight manual. The flap settings included are the result of the manufacturer’s test flights and any limitations put on the design during FAA certification.

Can a Plane Land Without Flaps?

In most aircraft, landing without flaps is not a big deal. It is considered an abnormal operation–it’s not a normal situation that you would do every flight, but it’s not an emergency either.

Flap versus no-flap approaches are probably indistinguishable to someone outside of the plane. A no-flap approach may require the pilot to fly a few knots faster on their final landing approach.

They may also use a few hundred more feet of the runway before stopping as a result. It’s also worth noting that the pilot will rely more on the brakes during the landing rollout since the airframe is making less drag.

Related Posts