The National Airspace System is complex. Getting your first pilot’s license is sometimes called your “license to learn.” For all the technicalities involved in flying a plane, manipulation of the controls is the easy part. SIDs and STARs are one element in a much larger system of routes that airplanes fly.

Table of Contents

SIDs, or Standard Instrument Departures, guide planes from the runway to the enroute environment. STARs, or Standard Terminal Arrival Procedures, guide planes from the enroute environment to the terminal environment, where they can join an Instrument Approach Procedure (IAP) that takes them to the runway for landing.

The instrument rating is the license that turns recreational pilots into professionals. During it, you learn all about how the pieces of the NAS connect together and how a plane can navigate through them all correctly. This is how airline pilots fly, and it’s a lot different from hopping in your Cessna and doing circles over your friend’s house.

Instrument Flying — An Overview

When a layperson hears the term “instrument flying,” they logically assume it means flying using the cockpit instruments. That’s correct, and indeed, that’s how the FAA defines instrument time. It’s time when the pilot is operating the aircraft solely by reference to the instruments.

That’s an essential skill to have in bad weather. When a plane is in the clouds, the instruments are the only things telling the pilot which way is up and which way is down. Those are pretty important things to know.

But pilots think of something different when they are out flying. Instrument flying to them means operating under instrument flight rules (IFR). Those rules lay out how they must operate the plane in order to operate in the clouds.

IFR versus VFR Flying

Once they’ve completed training and have some experience, the pilot doesn’t pay much attention to how they’re operating the airplane. In the real-world environment, there’s a little bit of visual and a little bit of instrument reference going on all the time. Planes pop in and out of clouds, so the pilot must constantly switch between the two flying types.

When talking about the rules, however, the two experiences are very different. VFR flying is like hopping in your car and driving to the store. You just do it, and you don’t need directions or help.

Instrument flying (IFR), on the other hand, is all about having constant help available. To be allowed into clouds, there has to be a way to keep planes away from one another. That means they all need to be talking to air traffic control.

An air traffic controller’s job is not to tell a pilot where to go or how to get there. Their job is to keep them away from other planes. But to do that, everyone has to be on the same page. ATC needs to know which way the plane is going and if it’s going to turn or change altitudes.

To simplify things for everyone, there is a very complicated highway system in the sky. You might think that planes go every which way, but they usually fly predetermined and charted routes.

Parts of an Instrument Flight

What are these routes? Pilots follow different segments from the minute they leave the ground until the minute they touch down. Each segment of navigation is presented on a different type of chart.

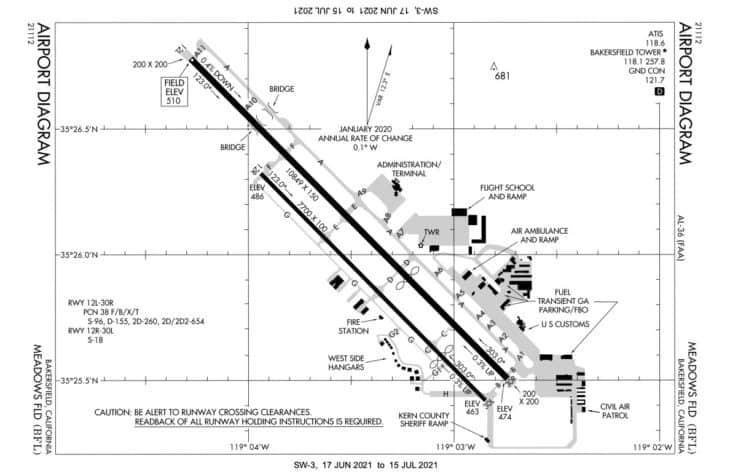

Airport Diagram

First, the pilot needs to be able to get from their gate or FBO to the runway. To do that, they use a simple chart of the airport surface. The ground controller in the tower will direct them to the runway by providing the taxiways they should take.

Departure Procedures

Pilots are given two types of guidance to help them navigate away from the airport safely. Together, these products are known as Departure Procedures (DPs).

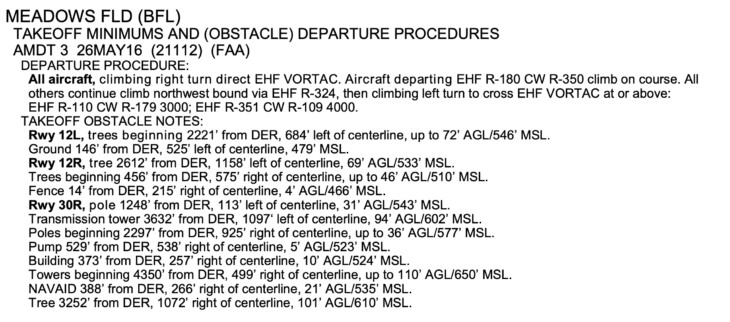

Obstacle Departure Procedures

The first type of DP is created to ensure that a plane safely clears all obstacles in the area. These are called Obstacle Departure Procedures, or ODPs. The ODPs are found in the beginning section of the Terminal Procedures Publication with the airport’s takeoff minimums.

ODPs are usually presented textually, but some very complex ones get a graphic chart as well.

Standard Instrument Departures (SIDs)

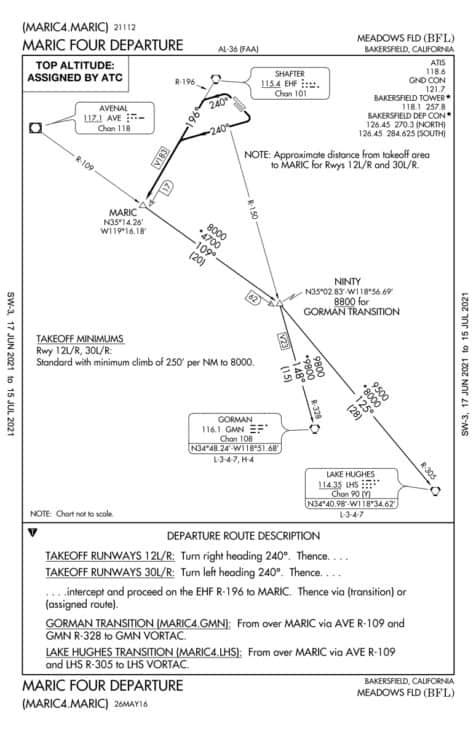

There may be departure routings in congested areas that are developed solely to aid air traffic control’s workflow. For example, it’s much easier for the controllers to say, “Delta 123 Heavy, join the MARIC FOUR departure,” than to spell out each course, turn, and altitude assignment.

SIDs are graphically depicted with their own charts. The pilot simply gets out the chart and flies the published route.

DPs typically end a major navaid, like a VOR or an RNAV/GPS waypoint. From there, pilots can use the enroute chart to navigate towards their destination.

En Route

En route navigation is based on radio navigational beacons called VORs (very high-frequency omnidirectional ranges). VORs are linked together with a system of airways. Below 18,000 feet, these routes are known as Victor Airways, and they all begin with a V- designation.

Above FL180, the VORs are linked by Jet Routes, designated with a J-.

VORs are becoming less critical as the airspace system switches to using GPS-based satellite navigation. The points remain, as do the airways. There are now GPS-only waypoints and RNAV (area navigation) routes that link them. RNAV routes typically begin with R.

Standard Terminal Arrival Procedures (STARs)

A pilot can navigate to a VOR near their destination using the airway system. But once closer, they’ll need to navigate to the airport. STARs simplify that process. A STAR is an arrival route. Most STARs serve several airports in one area.

Like the enroute flying, a STAR might be based on VORs or RNAV/GPS routes.

Instrument Approach Procedures (IAPs)

When the weather is good, air traffic controllers vector a flight close enough to the airport that the pilot can see it. When they have the runway in sight, the pilot is cleared for a “visual approach.”

But what if there are low clouds? In that case, the pilot must fly an instrument approach procedure, or IAP. The IAP takes the pilot from the STAR or the enroute environment directly to the runway for landing. Examples of IAPS include ILSs, VOR approaches, and GPS/RNAV approaches.

Who Assigns SIDs and STARs?

The final authority for a flight is the pilot in command, but the pilot generally needs to do what they’re told in IFR flying. Nine times out of ten, SIDs and STARs are assigned by the air traffic controller.

But nothing that a pilot is told to do during a flight should come as a surprise. If the pilot has studied their route beforehand, they should be aware of the possible SIDs and STARs between their departure and destination airports.

If one of those SIDs or STARs looks convenient, they can include it on their flight plan.

Instrument flying planning is different from VFR planning in that the air traffic controllers get the last say. They may know things that pilots don’t, like that due to the wind conditions today an alternate STAR is being used.

How to Read SIDs and STARs

If you know how to read an IFR en route chart or an approach plate, reading a SID or STAR is fairly straightforward. Many of the same symbols and notations are used.

Example 1 — MARIC FOUR DEPARTURE, BAKERSFIELD, CA

Here is a SID for Meadows Field in Bakersfield, California (KBFL). The name of the SID is the Maric Four Departure — this is what air traffic control will call it if they cleared a pilot for it.

The “four” is a revision number. This one will become obsolete when something changes, and the MARIC FIVE Departure will be in effect.

Notice that the chart has two panels. The upper describes the procedures graphically, and the lower describes the same using text.

If you start with the text, you can work through the steps of the departure. For example, if a pilot is departing from runway 12L (left) or 12R (right), the will turn right to a heading of 240º, then “intercept and proceed on the EHF R-196 to MARIC.” Say what? Let’s break that down.

If you refer to the graphic, you’ll see that EHF is the Shafter VOR. Courses away from VORs are described as radials, so the guidance tells you to intercept the 196º radial outbound.

MARIC is a fix located where the Shafter 196º radial intersects the 109º radial from the Avenal (AVE) VOR. The location of MARIC can be identified by distance from Shafter (17 DME) or by GPS using the coordinates given (N35º 14.26’, W119º 16.18’).

The next phase of the departure depends on which way the flight is heading. There are two transitions — one ends at the Gorman (GMN) VOR and the other at the Lake Hughes (LHS) VOR.

Both transitions take the plane to the NINTY fix. From there, the flight either heads towards GMN or LHS.

Beyond the VOR radials and courses that must be flown, the SID depicts essential altitude requirements.

From the airport to MARIC, there are not altitudes specified on the chart because the plane is climbing. There is a note about takeoff minimums, though. It says when departing, the standard minimums apply if the plane can climb 250 feet per nautical mile (NM) to 8,000 feet.

After MARIC, minimum altitudes are spelled out. The minimum enroute altitude (MEA) after MARIC is 8,000 feet. If on the Gorman transition, NINTY must be passed no less than 8,800 feet. The minimum altitude to Gorman is 9,800 feet, and the minimum to Lake Hughes is 9,500 feet.

An asterisk precedes some altitudes. For example, the minimum after MARIC is 8,000 or *4,700 feet. These are MOCAs or Minimum Obstacle Clearance Altitudes. These provide clearance from terrain, but they do not guaranty that the plane will be able to receive the Avenal and Shafter VORs.

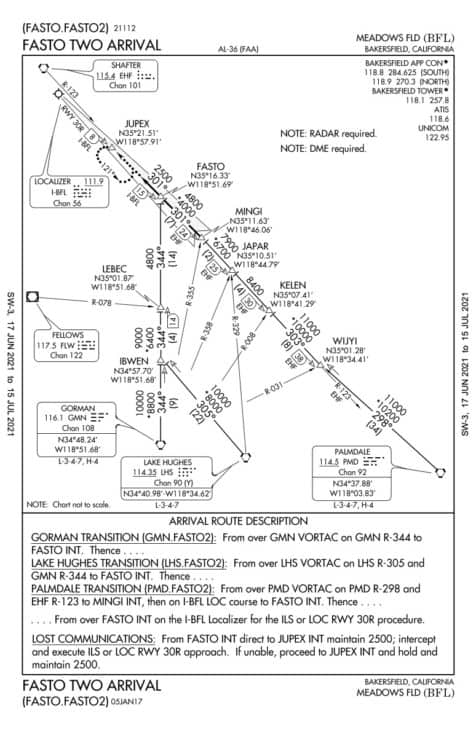

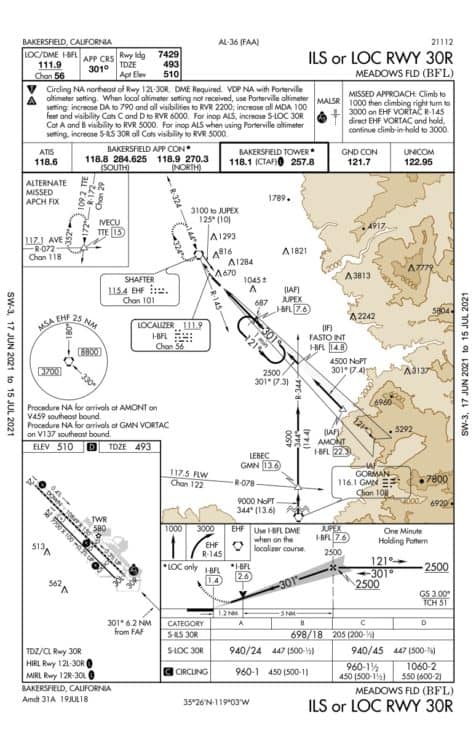

Example 2 — FASTO TWO ARRIVAL, BAKERSFIELD, CA

Here’s a look at the STAR coming into Bakersfield. The first thing you’ll notice is that it looks very similar to the departure.

STARs begin with transitions. In this case, a pilot could be arriving from the Gorman (GMN), Lake Hughes (LHS), or Palmdale (PMD) VORs.

In each case, a course and altitudes are provided to navigate the pilot to the fix FASTO.

FASTO is a fix defined on the Runway 30R Localizer (I-BFL). On that course line, it’s at 15 DME distance. It’s also where the localizer intersects with the 344º radial from the Gorman VOR (GMN R-344). GPS coordinates are also provided.

Since FASTO is a fix on the localizer, the pilot can then fly the ILS or LOC approach straight into runway 30R.

How to Find SIDs and STARs

SIDs, STARs, and IAPs are published in the Terminal Procedures book. Together the charts make up what most pilots refer to as the “approach plates.”

All of these charts are widely available in digital format. The FAA’s Aeronav website has all of the Digital-Terminal Procedures Publications available for download. Commercial sites, like Airnav.com, provide links to the charts for each airport. Apps like Foreflight include downloads to current charts with their flight planning tools.

Jeppesen also publishes instrument charts. Professional pilots commonly use these charts since they have a reputation for being slightly easier to use and read. The charts depict the same features, but they use slightly different symbology and layouts.

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)...

- English (Publication Language)

- 392 Pages - 01/01/2013 (Publication...

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)...

- English (Publication Language)

- 312 Pages - 11/28/2017 (Publication...

References ▾

Related Posts