The technology found in the cockpits of small planes comes to us thanks to the trickle-down effect. Flashy new toys start in military cockpits, then transport category aircraft, and finally general aviation. By the time it hits GA flight decks, things have gotten miniaturized and much cheaper. Take, for example, the yaw damper.

Table of Contents

A yaw damper is an autopilot feature found on more and more planes. It controls the rudder and applies corrections anytime the system detects slips or side-to-side G forces. Each plane is different, though, so you should always refer to the operating handbook for when to use the yaw damper and when to switch it off.

How Does a Yaw Damper Work?

The yaw damper autopilot feature is found on many aircraft. It became necessary with swept-wing aircraft, which needed help with stability. On those planes, the yaw damper helped control a dangerous tendency known as dutch roll.

But today, the technology is found on even small planes, like the Cirrus SR-22 or some Beechcraft Bonanzas. So what is the purpose of yaw damper on small planes? In these cases, the yaw damper provides a smoother ride.

One confusing thing about the yaw damper is its name. The name is a misnomer, it should perhaps be called the slip damper. Yaw is a necessary control direction of flight accomplished with the rudder. The yaw damper doesn’t eliminate that or dampen it.

Instead, the yaw damper works like an extra set of feet on the rudder pedals that operate automatically. Accelerometers monitor the aircraft’s motion, and the autopilot moves the rudder just the right amount to counteract that motion. So it applies the rudder on its own to make small corrections, relieving the pilot’s workload.

Why Do Some Aircraft Need Yaw Dampers?

Sometimes, the yaw damper is an advanced autopilot system designed to reduce pilot workload and give the passengers a smoother ride. But in other cases, the yaw damper is a necessary feature of the plane’s safety system to prevent the onset of a severe dutch roll.

Slip Prevention and Ride Quality

Most general aviation aircraft only have single or two-axis autopilots installed.

Single-axis units are commonly called wing levelers because all they control is roll. On these planes, the pitch is easily trimmed for hands-free flying.

Two-axis systems add the ability to control pitch. That usually means an electric servo that controls the pitch trim. It means an autopilot that can climb or descend to an altitude and then level off there.

Only if a yaw damper is installed can an autopilot have three-axis control. Traditionally, this hasn’t been encountered until you get into turboprops or jets.

But better autopilot systems mean that this technology has trickled down. Now quite a few light singles also have yaw dampers.

In these cases, the plane is perfectly stable without the yaw damper. But the fancier autopilot makes it easier for the pilot to control.

The electronic control also produces a smooth ride for passengers. The sensors that make the yaw damper are sensitive, and it can make very small corrections very quickly.

Dutch Roll Yaw Damper

If the damper is installed to tame dutch roll, it might also be called a stability augmentation system (SAS).

Yaw dampers didn’t become necessary until jet-powered aircraft with swept wings hit took to the skies at high altitudes. Famously, it was the Boeing 727 that highlighted the importance of these devices.

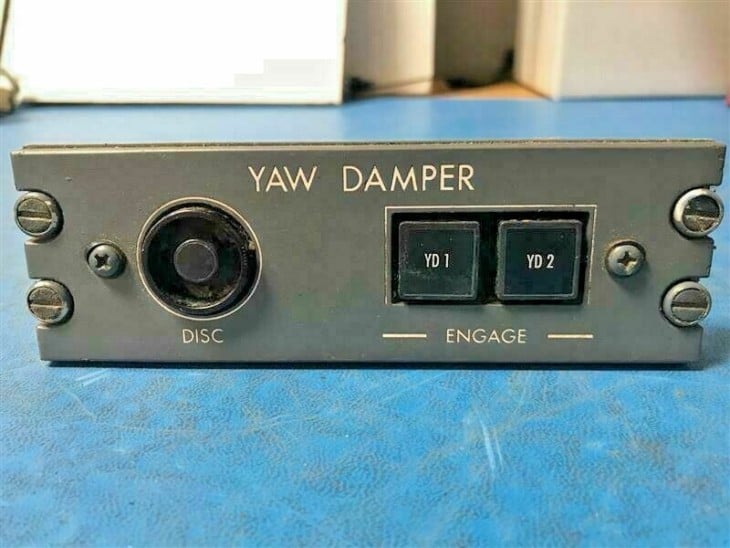

The yaw damper was so important on the 727 that the aircraft had two systems installed, one for the upper and one for the lower rudder. They were minimum required equipment.

Pilots were told that if both dampers failed, the plane would be uncontrollable and crash if flying above FL350. So most pilots chose not to fly their 727s above FL350.

If a single yaw damper failure occurred, the handbook and emergency procedures required an emergency descent to FL260.

What is Dutch Roll?

Another name for Dutch roll is free directional oscillations. That gives you a pretty good idea of what the problem looks like.

According to the FAA’s Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge, Dutch roll is a connected lateral and directional oscillation. It’s stable, meaning that once developed, it might not stop. But because it’s an oscillation—going one way and then turning the other—it’s unsafe.

When dutch roll occurs, it starts with one wing getting pushed down—perhaps due to turbulence or perhaps a control input. The resulting sideslip stabilizes the wing and brings it level, which happens faster than the nose coming back into the relative wind.

Since these two corrections happen at a different rate, the nose of the plane is swung in a figure-eight in the sky.

Most airplanes come out of the dutch roll quickly. But high-altitude swept-wing aircraft are very susceptible.

Any plane with significant dutch roll tendencies usually comes with a yaw damper.

When Should You Engage a Yaw Damper?

If your plane has a yaw damper, there’s only one place to answer questions like “can you land with yaw damper on”—the Pilot’s Operating Handbook, or POH. We can only draw some generalizations here because each plane’s design and installed system are different.

Most systems found on small planes today automatically turn themselves on at certain altitudes, usually immediately after takeoff until right before landing. That way, the pilot doesn’t have to worry about it.

Transport category aircraft are different, though, and these usually require the pilot to activate and deactivate the system.

Taking off or landing with yaw damper on is a bad idea. On multiengine aircraft, the yaw damper could mask the yaw effects of an unexpected engine failure. On landing, the pilot may find the aircraft less responsive than necessary to fight crosswinds and during the flare to touchdown.

References ▾

Related Posts